COVID-19 and African Immigrants in Maine

Maya Wasserman

Beginning in 2010, violence and unrest in the Great Lakes region of Africa attracted a wave of asylum seekers from Central Africa, including the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), Angola, Burundi, Rwanda, and Zambia, to settle in Maine, drawn to the state by its reputation for friendliness towards immigrants. In recent years, this trend has only heightened, and in June 2019, Maine made national news for welcoming over 300 Congolese and Angolans in the span of just a few days.

As the Central African community in Maine continues to grow, immigrants continue to encounter a profoundly different religious culture in their new home state than in their country of origin. While the nations of central Africa are some of the most heavily Christian on the continent and in the world, Maine is a highly irreligious environment. In the Democratic Republic of the Congo, a major source of asylum seekers entering Maine, 94.9% of the population claims a Christian affiliation. In Maine, only 25.9% do.

How have Central African churches in Maine responded to COVID-19? How have their unique experiences shaped their views of the virus and the policies surrounding it? The following exhibit presents several sermons given by pastors in the Central African community. Within these sermons, three themes emerge that illuminate the community's response to the pandemic.

A Global Perspective

"We have overcome. Even Ebola we have overcome. Even coronavirus we are going to overcome. And I’m going to ask you to stand up, all of you here today. The worship team come forward here. And we are going to pray for coronavirus. We are all going to pray that God is going to help us. Help our nation here in the United States, the nations where we came from, and the whole world." -Rev. Peter Mutima

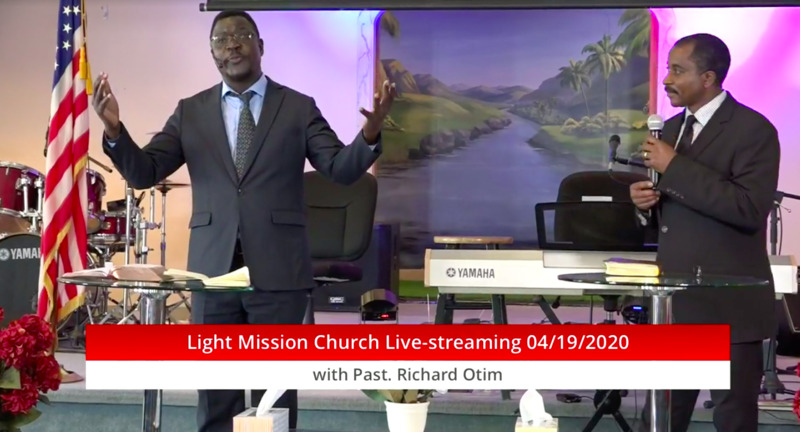

"When you listen to only the COVID virus killings, it’s even becoming more. You find that in some countries even hunger is killing people. In some countries we hear even Ebola is killing people. In some countries you hear the Bird flu is killing people. The times are so hard." -Richard Otim

Central African churches in Maine tend to have a broader, more global perspective on public health, religion, and the pandemic. Since the discovery of the Ebola viruses in the Congo in 1976, there have been 18 recorded outbreaks in Central Africa, more than in any other region. In addition, the DRC has faced at least five outbreaks of cholera since 2002. Central African immigrants living in Maine likely have in their recent memory other epidemics with which they can compare their current experiences of COVID-19. They also are likely aware of other problems going on in the world and in Africa that American-born Christians may not know about, such as famine and bird flu. Preachers point to these recent and co-occuring issues, placing coronavirus in a global and historical context.

"Many churches were closed today. In Rwanda, no churches were open today. And so many others. Back home, somehow, they don’t even have enough equipment to protect themselves. But now, I know our God, the God who never abandons, and God of all time." -Peter Mutima

"COVID-19 is killing people. For the first time I am hearing that 40,000 people have died. For the first time, I'm hearing the news in another country, 100,000 have died. If you listen in a day, you will hear 1,000 people lost their lives. I was turned to tears when I saw that in Italy there was nowhere to bury people." -Richard Otim

Central African preachers also tend to demonstrate profound awareness and sympathy for not just the effects of COVID-19 in Maine or the United States, but across the world. Central African nations such as the DRC have very high rates of emigration, especially since regional instability increased in the 1990s and 2000s. Subsequently, Congolese, Rwandans, and other Central Africans make up large diasporas that reach throughout Europe, Africa, and North America. More than many American-born Mainers, they may have family and friends scattered across several different countries. Many of the sermons found have a high degree of sympathy for the global toll of COVID-19, and often call for prayer directed beyond the borders of the United States.

Trust in God, not the Authorities

"We have to think about what is happening. This is just a case of the disease. This is just one thing that is separating us again. . . Just because of this disease. But when the authority can make even the decision that all the churches should close down completely, that they should remove the social media, nobody can preach on social media, nobody can come and speak about Jesus so openly, what are you going to become?" -Eddy Kadima

"But let me tell you today: the war that is coming upon us, the victory in this war, will not come from man. Will not come from the authorities. Or from all the people that talk about viruses. Or the biologists. Or the doctors. Or from the hospitals! No! The victory against this war, against this pandemic will come from the Lord." -Achille Nsumbu

Several of the sermons analyzed discuss the need to be wary of authorities such as the government, doctors, and scientists. Instead, they encourage their audiences to put their trust in God. Many preachers not only dismiss these sources of authority as less powerful than God, but actually caution their listeners to be aware of active government maleficence. For example, Eddy Kadima at ADS Church in Lewiston points out the precedent being set of government ordering churches to close, and predicts the regulation of religion on social media. Many Central African preachers similarly emphasize independence from traditional authorities such as doctors and politicians, more so than other preachers in Maine.

"I know God helps through people. But our ultimate help must come from God. Trust him. And now is the time to turn to the Lord. Now is the time to repent our sins. Forgiveness and cleansing is ours when we repent. Brothers and sisters, not washing our hands, we need to wash our hearts, We need to wash our lives. We need to cleanse our lives." -Richard Otim

The national origins of the preachers and congregants in Maine Central African churches may contribute to this mistrust in government authority. African immigrants to Maine, especially in recent years, have escaped repression and corruption in their home countries. In 2019, DRC was ranked 168 out of 180 countries for the worst corruption, while Burundi ranked 165, and Angola ranked 146. In addition, African immigrants must usually go through notoriously lengthy and difficult processes of applying for asylum once in the United States, which may only add to disillusionment with the idea that the authorities have their best interests and protection at heart, accounting for strong messages of trusting in and focusing on God and the church while turning away from secular authority.

Apocalyptic Messages

"There is nowhere where we are told in the last days it will be peaceful. And there is nowhere where it is written that people who believe in God will have peace. But we have something beyond what other people have. We believe and trust in God." -Peter Mutima

"This is a moment of reflection, this is a moment that we need to take time to think about what is going to happen at the End of Time, because we all know that situation will be difficult, that many people won't be able to talk together and pray together." -Eddy Kadima

Several of the sermons cover apocalyptic themes that either describe the current pandemic as a sign of the apocalypse, or urge their audiences to treat it as preparation for the apocalypse when it eventually comes. These ideas often contrast, even within the same individual sermon, with the previously discussed themes of overcoming the virus through previous experiences with pandemics. For example, Peter Mutima both refers to the present as the "last days" and reassures listeners that they will get through coronavirus just as they did Ebola. This raises the question of whether sermons preached during past Ebola and other outbreaks had similar themes, or whether they approached the disease and its effects differently.

"After this time, God will establish His church. God will put order in His church. When it ends, you will see some of the churches will remain empty... The churches where they had so many members, but Jesus wasn’t with them, they will be empty! There is a putting upside-down of the situation. And in every plague that happened in the Bible, God came for the reestablishment. And that’s what is going to happen." -Achille Nsumbu

Other preachers take a slightly different approach, portraying coronanvirus and the challenges of church closures as not a sign of apocalypse, but a cleansing on earth. In this view, the pandemic is a trial that only the most righteous of churches and religious organizations will survive. Again, was this type of rhetoric used during past Ebola outbreaks? And what kinds of churches do pastors like Nsumbu feel are lacking and will be permanently shut down by God?